Dear readers,

KOMMON was founded during the midst of the worst of the COVID-19 global pandemic. There was a perfect confluence of an increasing global interest in Korean affairs with the increase in people spending a higher percentage of time at home. Given that KOMMON is a not-for-profit entity, our staff worked hard due to their dedication to the end product.

When the world began to take major steps toward reopening in 2022, this dynamic shifted. Although people continued to express interest in learning more about Korean politics, history, and culture, the reduction of social distancing regulations meant that our all-volunteer staff had an increase in other responsibilities.

At KOMMON, we seek to create high quality content for readers and foster a healthy work environment for our staff. To continue producing content with fewer staff members than needed would seek to threaten both of these goals. Rather than succumb to that future, this will be KOMMON’s final newsletter.

We are planning on uploading all previously-published newsletters. To check out our archive, please follow us on social media to keep up-to-date with this progress.

Our final newsletter will follow a special format. Members of the KOMMON team are going to recommend a topic pertaining to Korea that they recommend watching over the next few years. Even as KOMMON ceases publication, it is our sincerest hope that your curiosity about Korean culture will continue to grow.

Thank you for everything.

Sincerely,

Fred McNulty

Editor-in-Chief

Sunny Um

Chief Operating Officer

Please note that any opinions expressed below are that of the individual writer and not KOMMON as a whole.

Fred McNulty, Editor-in-Chief

South Korea has been home to the world’s lowest birth rate for the last decade. There is a bevy of causes behind this, from high costs of living, misogyny, and the general decline in fertility in advanced countries. In order to combat the looming economic threats of a declining population, increased rates of immigration are being discussed. However, life for non-Koreans residing in the country can be difficult at times. These range from minor issues such as names being longer than four characters causing problems, to the abuse of migrant labor and a ban on non-citizens engaging in political activity. It will be important to observe what the country does to better integrate non-Koreans into Korean society.

Yul Jun, Senior Operations and Logistics Manager

What is the price of a person's life? This is a question that is not easily answered. However, we can determine the value of a life lost due to industrial accidents in Korea. In 2020, the Korean court imposed a total fine of ₩1.68 billion for industrial accidents resulting in deaths. If we divide this amount by the number of fatalities, it comes out to be ₩8.69 million. As this number suggests, Korea is a country that is very lenient towards corporations when it comes to industrial accidents, but does not adequately protect the rights of workers. As a result, Korea ranks among the top in terms of occupational accident fatality rates in OECD statistics each year.

Various laws have been enacted to address this problem. The "Kim Yong-kyun Act," implemented in 2020, aimed to strengthen safety regulations at industrial sites. The "Workplace Disaster Law," which punishes CEOs for industrial accidents, came into effect in 2022. However, despite these laws, they have not been able to produce the desired effect. Workplaces are still unsafe, and industrial accidents, big and small, occur every day. Last October, a worker in their 20s died while working at an SPC bread factory, causing a lot of public outrage.

In this situation, President Yoon recently announced an increase in the maximum legal working hours to 69 hours, which caused public discontent. The issue of worker rights in Korean society must continue to be monitored to see how it will develop. If we keep an eye on it together and show interest, perhaps we can make some progress in a better direction.

If you're interested in this topic, it would be great to watch these movies together: Another Family (또 하나의 약속, 2014) and Next Sohee (다음 소희, 2023).

Regine Armann, Senior Editor

South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol visited Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida for the first bilateral summit between South Korean and Japanese leaders in over a decade earlier in the year—but opinion is divided over whether their meeting should be seen as a major (and necessary) step toward renewing relations or as “self-degrading diplomacy” and a humiliating victory for Japan, especially as it follows a widely criticized compensation scheme that will be funded by South Korean companies who profited from forced labor during the Japanese colonial period, prevents liquidation procedures of assets, and only “encourages” Japanese companies to join in.

President Yoon insists that Korea-Japan relations must leave the past behind, and most international media, especially those in the US, see the summit as a sign of rapprochement that is needed in the context of an increasingly aggressive North Korea and China’s growing presence in the Indo-Pacific region. However, many South Koreans struggle with the feeling that Japan does not deserve forgiveness or even the kind of pragmatism President Yoon seems to expect from them. Japan has issued several apologies to Korea over the years, but they are not perceived as specific and sincere enough by many and were not followed by concrete actions. Critics of the recent meeting have also pointed out that the key question of Korea’s “comfort women” and the dispute over Dokdo were not brought up at all, and the main opposition party has even threatened to open a parliamentary investigation over suspicions that Yoon might have made secret concessions.

As a German whose country is often cited as the go-to example of how Japan should have behaved since WWII (see also this article for a more detailed historical comparison and this thought-provoking piece on the power of forgiveness), I can only hope that South Korea and Japan will one day come to terms with their shared history and their shared responsibility for the future of both countries. Following the recent developments also reminded me that like South Korea, the German post-WWII population was divided over the question of guilt and responsibility—as were, I imagine, the citizens of the countries surrounding us. But the first ground-breaking decisions were not made by individuals or on the basis of opinion polls, they were made by and among politicians, in the best interest of their countries and the region at large.

Yoon for one seems to be determined to ignore criticism and faltering approval ratings and insists that it is his duty to mend Korea’s ties with Japan, its closest ally. We will see if he is shaping the future or if he has just built a hill for his personal political ambitions to die on. In the meantime, dig into this essay collection for more insights and creative approaches to the resolution of the Japan-South Korea tensions.

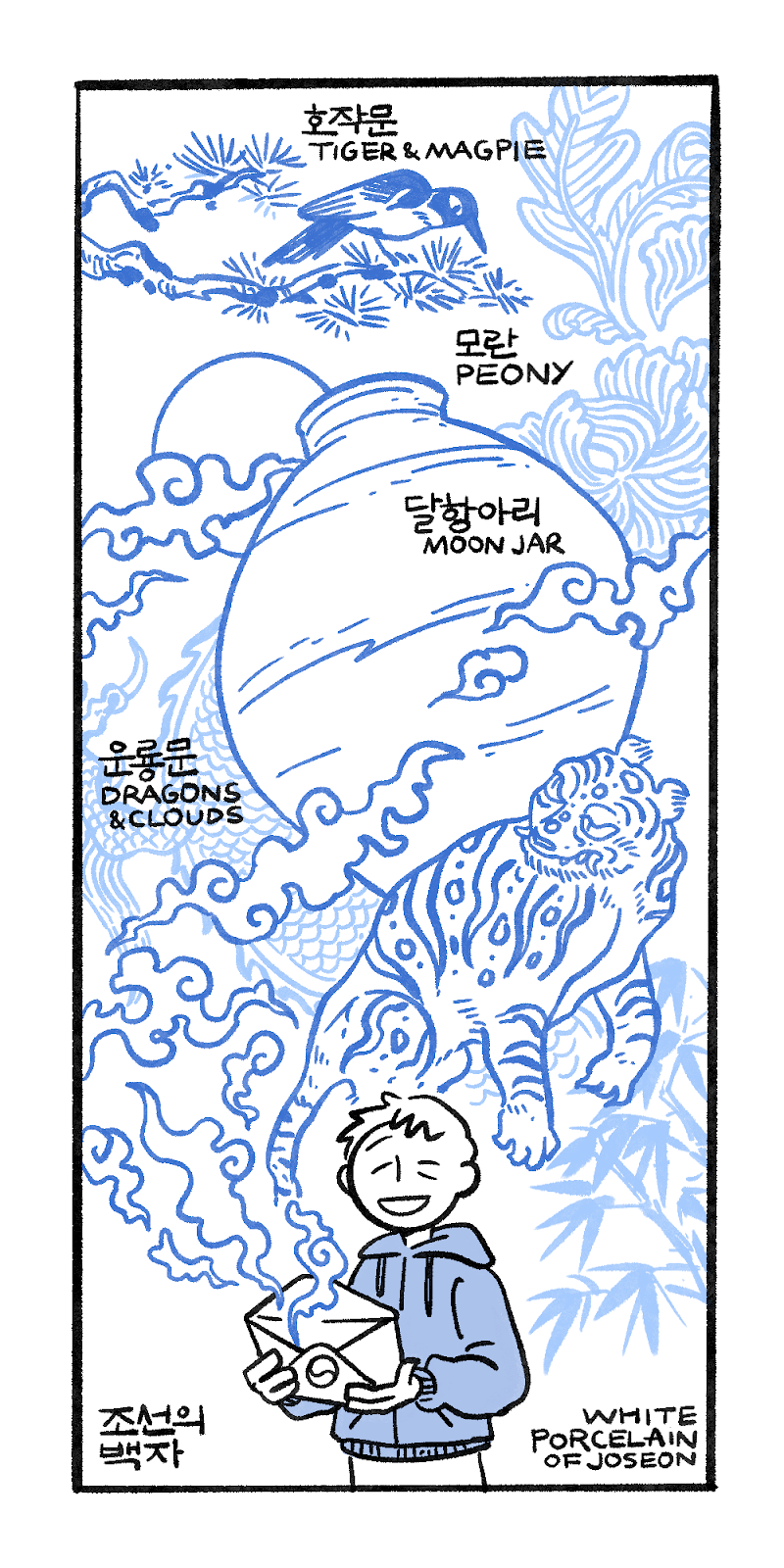

Ah-young Kim, Graphic Design Produce

Leeum Museum of Art in Hannam-dong, Seoul, is holding a special exhibition that focuses on baekja (백자), or white porcelain. “Joseon White Porcelain, Paragon of Virtue” (until May 28th) covers the full spectrum of Joseon white porcelain, with a special section titled “Pinnacle” that features 31 out of 59 porcelain works officially designated as cultural treasures by the Korean government.

As an illustrator for KOMMON, I am sending this final newsletter off with an illustration featuring several memorable designs from those 31 pieces. The dragon in the clouds (운룡문雲龍文) is often featured in cobalt-blue-and-white porcelain of early Joseon to signify the dignity and authority of royal court. The tiger and the magpie (호작문虎鵲文), on the other hand, appear by late Joseon period as an adaptation of the popular folk painting motif. They indicate a shift toward the popular and humorous, as white porcelains were made more widely available to the public.

The middle of the illustration features a moon jar, which is perhaps the most well-known shape when it comes to Joseon porcelain. The wide opening, the rounded curves that swell somewhat unevenly in the middle, and the narrow bottom creates an illusion of the jar itself floating in the air, much like a full moon in the night sky. The moon jar has often been featured in the works of modern Korean artists such as Kim Whan-ki, who wrote in 1955: “Warm steam seems to rise from cold porcelain. How did human hands endow clay with living warmth?”

At Leeum Museum’s “Pinnacle,” visitors weave through the darkened exhibition space, stopping at each subtle glow of white porcelain until they reach three large moon jars on the far side of the room. It is then that the visitor is made to look back the way they came―and feel as if they’re suspended in a starry sky where each light of well-worn, shining porcelain carries centuries of touch and care. As KOMMON comes to a close, it is my hope that the reader would continue to look into Korean culture.

Daeho Park, Writer

The household credit balance at the end of last year in Korea reached a staggering ₩1,867 trillion. Combined with the debt from jeonse (전세) deposits, the total surpasses ₩2,925 trillion. Jeonse is a unique form of lease deposit in the South Korean real estate market. Despite acting as a debt in practice, jeonse deposits are not officially recognized as such. Consequently, the average person now carries a deficit of over ₩57 million, primarily driven by a significant five-year increase in housing prices.

As the world enters the post-pandemic era, Korea ranks fourth among OECD countries in household debt-to-GDP ratio; however, if jeonse deposits were included, it would become the highest. Notably, household loans continue to rise, with over ₩18 trillion in new loans issued in March alone, marking an 86% increase compared to the previous year, as the Bank of Korea reported. Although current interest rates have declined by approximately 1%, Korea's diverging monetary policy direction compared to the rest of the world, along with a significant base interest rate gap with the US, raises concerns for the future. The pressing issue of excessive household debt may eventually lead to a burst, although the potential impact remains uncertain.

Aleya Sharif, Staff Editor

Korean beauty standards have been a topic of discussion for many years. In fact, according to an article by the Harvard Medical Student Review, 46% of Korean female college students have undergone plastic surgery of some sort, the most popular procedure being double eyelid surgery. The influence of plastic surgery is so deeply rooted within Korean culture to the extent that it has become a popular choice of graduation gift by parents as well. However, with the ongoing influence of K-pop both locally and globally, there is a gradual and promising shift towards the perception of beauty in South Korea, especially amongst women.

Artists such as Jessi (solo artist) and Hwasa (from MAMAMOO), for example, are breaking stereotypes by promoting a healthier, more curvaceous body image. Given the predominant influence of K-pop on such a wide demographic, it is important that idols like this exist and are spreading such a wholesome and positive influence on the younger generation.

Jessica Dharmaputri, Senior Content Creator

While dramas and movies are generally a source of entertainment, it is without a doubt that they carry a lot of value in being an accessible way to learn more about Korean society. Many topics we’ve covered in our newsletter have derived from them, such as the edition on the real Woo Young-woos and the deep dive into the June Democratic Uprising born out of the K-drama Snowdrop. Hence, beyond the entertainment factor, I hope that our readers will continue to take a critical view into the topics and issues that these dramas and movies bring up, for they not only give insight into what’s currently important in Korean society but also what’s not talked about enough.

Our thanks goes out to Andrew Kim (Strategic Alignment Manager), Lanya Banerjee (Staff Editor), and Loren Sarenas (Staff Researcher).

Thank you.

Sincerely,

KOMMON

Since this is the last letter we send, please leave us your message for the last time!

👇

의견을 남겨주세요